When I was 20, a long time ago now!, I went to my GP feeling sick, with symptoms that included a sore throat, fever, a stuffy nose, and headaches. He quickly diagnosed me with a throat infection and prescribed a course of antibiotics.

More than a week later, having finished the antibiotics, and, having not improved but gotten worse, I went back to see him. He referred me for blood tests, and I waited for the results.

By this time I was climbing the walls, unable to sleep thanks to a severely swollen throat and an utterly blocked nose that made breathing feel almost impossible, especially when I was lying down. It was Brisbane summer, but even during the day I was so cold that I started locking myself in my car in the sun as my only means of warming up.

The blood test came back positive for Epstein-Barr virus, and the GP told me I had, not a throat infection, but glandular fever (some readers outside Australia might know it better as mononucleosis, or mono).

The worst of the virus lasted almost four weeks, but I didn’t feel like I fully recovered for several months after that.

The period I was on antibiotics definitely made things worse. During that week or so, I developed a rash and couldn’t unblock my airways, with a sensation like constant dripping from a tap running down the back of my throat.

In researching to write this piece I learned that: A more intense and extensive cutaneous eruption (the dripping) appears in up to 90 percent of patients with infectious mononucleosis 2–10 days after starting antibiotics.

There have even been papers published about Amoxicillin-associated rash.

Would I have gotten better more quickly if the GP had diagnosed me with glandular fever the first time I saw him? Would my symptoms have been less severe?

You could easily make the case that it’s impossible to tell. But I did feel worse after starting the antibiotics. I did get that rash. And the rash did disappear not long after I had finished off the antibiotics themselves.

The misdiagnosis in my view was telling. But, again during my research for writing this story, I learnt that it isn’t uncommon when discerning glandular fever from several other illnesses and conditions.

And so it is for Autism – a hidden disability. One it seems many clinicians, because of a lack of training and awareness, don’t even consider when a patient presents to them.

But that still doesn’t mean you shouldn’t seek a formal diagnosis for Autism if you’re able to.

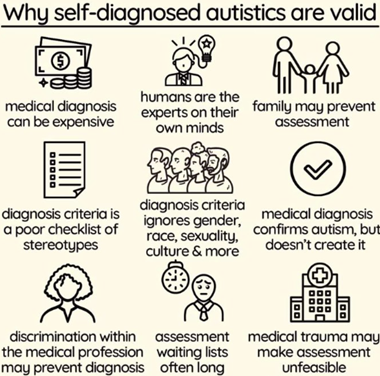

Reasons for choosing to self-diagnose as Autistic

I know that for a lot of people just the suggestion that you should consider seeking a formal diagnosis for Autism will be difficult to stomach – especially depending on what part of the world you live in, your gender, race, or culture. That’s why I’m covering this section first.

So let me say right off the bat that self-diagnosis of Autism is valid.

There are so many reasons not to chase a formal diagnosis, and if you are Autistic, or suspect that you are, then the mere thought of upsetting the potentially delicate balance of your life and subjecting yourself to a diagnostic process that defines and describes a person’s level of Autism by their deficits, not their strengths and abilities, can be a difficult sell.

I’ve been through it, and I dare say the confronting nature of the experience did little for my Autistic burnout and associated anxiety and depression.

We unfortunately live in a world that largely rejects, and can at times be completely intolerant to, difference. And Autism is an all-encompassing difference for the Autistic person, whether or not you have a formal diagnosis, or even know that you’re Autistic to begin with.

We also live in a world constructed around a version of normal that is out of step in so many ways, but one that most of us (I’ll include myself here because for 52 years I tried like hell – and often ‘failed’ – to live up to that idea of ‘normal’) seem willing to die and to kill for.

The world can be a scary place for those of us who don’t measure up to ‘the ideal’, who won’t or can’t conform to the views and expectations of others. And this can make many people, especially older people who have lived half (or more than half) of their lives suffering in silence because they weren’t diagnosed as a child, and because they’ve gotten so good at hiding who they really are.

Burying or suppressing the Autistic person you don’t even know that you are, through masking or camouflaging, means that the signs and characteristics of Autism aren’t obvious to the people around you – even those you’re closest to. But that doesn’t mean that you don’t know, deep down, that you’re hiding something, a difference that has either kept you isolated or attracted you to others who may also be neurodivergent.

Formal diagnosis of Autism is expensive, can be traumatic because of the inadequate, ‘narrow’ diagnostic criteria, and invalidating for so many reasons; not least, some of those I’ve already outlined, including our ability to ‘blend in’ and, notably, difficulty finding clinicians who actually know what to look for when diagnosing someone as Autistic. My own referring psychiatrist didn’t actually believe I was Autistic (but rather possessed “Autistic traits”) and only referred me on for further evaluation because of my own insistence.

Not everyone therefore will have the means, or feel that putting themselves through the scrutiny and potential prejudice of exploring an Autism diagnosis is right for them.

And, unlike me, you may simply feel a formal diagnosis isn’t necessary because your own belief that you’re Autistic is enough.

So what are the benefits of getting a formal Autism diagnosis?

I had been thinking about writing on this topic for a while, as a result of my own experiences, and after reading a lot of material this year, including a book by adult neuropsychologist Theresa Regan, who also happens to have an Autistic son.

But what prompted me to write this story this week was my wife telling me about a recent study in England that estimates more than 9 in 10 Autistic people aged 50 and older may be undiagnosed.

I’m sure this situation is mirrored worldwide, including in Australia where I am. And as someone who, until recently, fell within this subset of undiagnosed Autistic people, I want to continue to raise awareness about Autism and let older Autistics know that they aren’t alone in feeling somewhat alien in this world.

For the study, lead investigator and professor of neurodevelopmental conditions at University College London in England William Mandy surveyed more than 5 million medical records between 2000 and 2018 to track when people received their diagnosis.

Results revealed that a diagnosis for Autism was far more common among children and adolescents than it was for adults, ranging from 2.94 percent of 10- to 14-year-olds – who, the study’s team suggests, are more likely to have access to the best diagnostic services – to only 0.02 percent of people aged 70 and up.

These findings are in keeping with the relatively recent emergence of Autism as a condition in its own right. Autism only appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980, with its inclusion very narrow in scope compared to the condition we know today.

(Incidentally, the criteria for Autism outlined in the latest iteration of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – the DSM5 – is, in my view, still sorely lacking and not reflective of the wide-ranging experiences of many Autistic people, so here’s hoping there is a massive leap forward when the DSM6 is released.)

As Theresa Regan explains in her book ‘Understanding Autism in Adults and Aging Adults’:

“In addition to the need for awareness of Autism in the absence of intellectual disability, there is a tremendous need for individuals who understand adult medical and mental health conditions to also be well-versed in the unique neurology of the Autism spectrum. Because of its developmental nature, much of the initial focus on Autism has been within the areas of paediatric medicine, early intervention services, and the school systems. Clinicians who specialise in Autism, therefore, are almost primarily paediatric specialists. Because Autism is a condition across the entire lifespan, clinicians who are expert in adult and geriatric care need to be just as expert as paediatric clinicians in the area of Autism diagnosis and services.”

But, as has been my experience, and I’m sure has been yours, this is very often not the case, and makes receiving a formal diagnosis difficult for so many older undiagnosed Autistics.

Still, despite everything I’ve already written in this article, if you do suspect that you might be Autistic, I say: Go for it! For me at least, the benefits far out way the negatives. But only if you are ready, emotionally, to stay the course.

The first chance I potentially had to be diagnosed Autistic actually took place not too many years after I was misdiagnosed with a throat infection rather than glandular fever, but with a different GP.

I had attended this time with a particularly nasty rash that the doctor attributed to stress, telling me further that I was suffering with depression, and, that I could be bipolar.

Uncomfortable with this idea, and not wanting to put myself through any more than I had to at the time, I promptly ignored his assessment and resolved to do nothing further.

Almost 30 years later, at the beginning of 2022, after a lifetime of trying to be the person I was “supposed” to be, I found myself at breaking point.

While I am actually glad now that I wasn’t diagnosed Autistic as a child, I am, in far greater measure, ecstatic that I have my diagnosis.

A long-lost but very good friend of mine recently captured the feeling better than I ever could when he wrote in an email to me: I’m happy you’ve found something you can point at and go – fuck that’s it. From that point the only way is healing and up I reckon. Obviously nothing’s ever easy but there’s no need to go around life asking yourself wtf is going on with me. (I don’t believe he’ll mind me including this. I hope not anyway! 🙂)

Misdiagnosis is perhaps one of the most insidious aspects of healthcare. While I’m not suggesting any health professional ever sets out to misdiagnose anyone, Autism, being as complex and misunderstood as it is, is rife for this type of outcome. It’s also especially likely in people who present without any intellectual disability, of which there are many, and particularly if you’re older.

It is generally a misplaced assumption that people are better served if we do not “label” them with a diagnosis. In my experience, people label each other regardless of whether it is with a diagnosis or not. The question is not whether an individual is described by a label or by a set of characteristics, but whether the description is accurate and helpful.

Theresa Regan ‘Understanding Autism in Adults and Aging Adults 2nd Edition’

Receiving a correct, formal diagnosis has allowed me to access services and benefits I wouldn’t have even been able to apply for if I’d stuck with self-diagnosis alone. I would not have been able to afford to see the health professionals I am now seeing, nor take part in the Autism courses I am now embarking on.

I also believe a formal diagnosis makes it easier (not guaranteed, definitely not that) for family and friends to reach some measure of acceptance that I am indeed Autistic, even if it’s still something that’s difficult for some (many?) to completely come to grips with.

It may also help non-Autistic loved ones, friends, colleagues, and employers understand why you experience certain things differently to them or need to draw limits with time and activities when they do not.

Receiving a formal diagnosis might allow you to safely stop taking medication you may have been using for many years for a condition you don’t actually have – medication that might be doing you little good or may even be harmful.

A formal diagnosis will definitely allow you to stop trying to be something and someone you’re not – and I can’t express in mere words in this here blog what a wonderful feeling that is and how healing it can be.

In short, any progress I’ve been able to make during these past months I largely attribute to my formal diagnosis and, consequently, the supports I have been able to access.

Hopefully, if you’re a regular reader, you will be able to tell through the stories I write, that there has been some positive development in terms of recovery from this current bout of Autistic burnout.

If you, dear reader, are someone who has never understood why you’ve struggled to navigate the world, perhaps it’s because you yourself are an undiagnosed Autistic adult. And the world is exclusively designed for non-Autistic people – not people like you and me.

Whichever way you go after reading this article, formal- or self-diagnosis, make sure you do take action to change your life where possible so that you start living it on your terms – as an Autistic person – to help reduce the risk of ongoing Autistic burnout.

I can speak from personal experience about the damage done to one’s mental health by sticking your head in the proverbial sand.

My own first steps to diagnosis included using some of these screening tools as a way of helping me decide if a more formal assessment would even be an option. Only after taking the Autism Quotient at least five times, and trying to be as non-Autistic as possible when it appeared (egads!) that I might actually be Autistic, did I seek out the referring psychiatrist I mentioned earlier.

Perhaps most importantly of all, find people to support you – not invalidate you – on your journey, read a blog like this one, or find and join an online Autistic community.

I hope that next year I will be able to expand my little website to include a podcast or similar, and add strings to the support I’m able to provide to older, late-diagnosed Autistic people.

But in the meantime I’ll do what I can here, and continue focusing on living my own life on my terms as much as is possible. Because ultimately, whether you get a formal diagnosis for Autism or not, that is, in my view, the best medicine.

Did you find this article helpful? Did it resonate with you or in some way make you stop and think? Writing these pieces takes time and effort, and your support can make a real difference in helping to keep this content flowing. If you enjoyed this post and would like to read more articles like this in the future, please consider donating a small amount to help me cover the costs of running this website. I’m not in this to get rich (and trust me, I won’t! 😉), but your contribution helps sustain the effort that goes into crafting fresh, Autism-friendly content. Your support is greatly appreciated. Thank you!

I really love your writing Glenn. I’m subscribed and I love it when I see one of your blogposts appear in my inbox!

Thanks Tish! I’m really glad you’re enjoying the blog. 😊 I’ll keep tapping away, too!