From a very young age, whenever I met someone new, I could tell within the first few minutes by the way that they moved and the tone of their voice and the suggestions they made, whether they were a person I could trust or not.

It felt, at the time, like somehow I could see into them and feel their intentions before they had even had a chance to manifest themselves – like I could tell, immediately and implicitly, whether they were “good”, at least for me.

While this ‘goodness radar’ made me judgmental in the extreme, it also saved me many times from unwanted situations I saw play out with less suspecting kids, some of them friends of mine, taken in by a smile and the lure of potential excitement.

This radar was also something I could weaponise when the moment called for it. For while I had my group of friends and was decent at sports, I was small in stature, and quiet, so sometimes found myself the target of bullies in the playground.

But no one, not even a kid twice your size, likes having their greatest fears and insecurities laid bare before a group of their peers. Something my radar, smart mouth and fast feet allowed me to use to my advantage.

Autism and the theory of mind myth

‘Theory of mind’ is a term that’s used to express a person’s ability to understand the beliefs, thoughts, intentions, and feelings of others. The widely held consensus has always been that these are skills Autistic people have problems with. Which means of course that I shouldn’t have been able to read people the way I could when I was a kid, or can today.

Research led by developmental psychologist Uta Frith and clinical psychologist Simon Philip Baron-Cohen – pioneers in this area – suggests that Autistic people have particular difficulties understanding another person’s point of view.

Baron-Cohen’s research further describes Autism as a disorder of ‘mind-blindness’, and in a 2004 paper as an ‘empathy disorder’, proposing that in Autistic people there is an imbalance between empathising and systemising, or the ability to understand how systems, rather than people, work. (He obviously hasn’t seen me try and do maths!)

Since first hearing about ‘theory of mind’, and before I had even embarked on the research I’ve so far undertaken (and there is a lot more I could still do) on this topic, it sounded like fantasy. Or, to put it another way: utter bullshit.

To give you an idea of the contempt in which Baron-Cohen and Frith hold Autistic people – people they profess to have, and in Baron-Cohen’s case, continue to help – I invite you to watch the video below.

In it, Frith cites a landmark paper from 1978 authored by David Premack and Guy Woodruff: Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?

In the paper, Sarah, an adult chimpanzee, is the subject of a series of experiments designed to assess her ability to attribute mental states including goals, intentions, knowledge, and ignorance to humans – something akin to a ‘theory of mind’, or ‘mindreading’.

Ultimately, after concluding their research, Premack and Woodruff determined that Sarah did in fact possess a theory of mind as a result of being able to attribute mental states to her trainers.

However, according to Frith, Baron-Cohen, and Scottish psychologist Alan M. Leslie, the same cannot be said for the majority of Autistic people.

Let me restate that as simply and clearly as I can: In the video, Frith is content with the idea that chimps have a theory of mind, but that most Autistic people do not.

Frith, Baron-Cohen, and Leslie came to this conclusion after testing for theory of mind via a false-belief test developed by Baron-Cohen and Frith – commonly known as the Sally-Anne test.

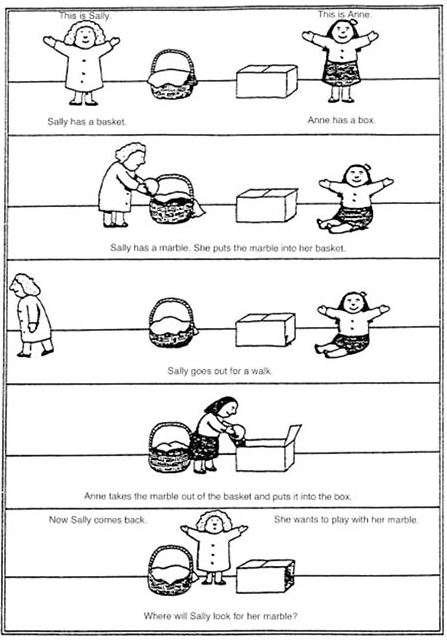

The test takes the form of a short role play where Sally takes a marble and hides it in her basket. She then “leaves” the room and goes for a walk. While she’s away, Anne takes the marble out of Sally’s basket and puts it in her own box. Sally returns and the child (the test subject) is asked the key question: “Where will Sally look for her marble?”

As someone diagnosed Autistic less than 12 months ago, and therefore new to the entire ‘Autism narrative’ – one that it’s clear to see has traditionally focused on Autism as ‘deficit and disorder’ rather than ‘difference’ – I come to this world with fresh, wide-open eyes as I seek to learn all that I can about my brave new existence.

But what I’ve largely discovered so far is, sadly, a rather sordid history. One that has dehumanised, tortured (this is still going on in the United States today, as is behavioural engineering or ABA), stigmatised, and marginalised Autistic people.

As a result, we often live on the fringes of society, placing us at increased risk when compared to the general population in areas that include mental health, employment opportunities, access to education and other services, and the criminal justice system.

There is clearly a well-established guard in Autism research circles (the likes of Frith and Baron-Cohen), whose lifework has looked to build upon that of George Frankl, Eugen Bleuler, Hans Asperger, and Leo Kanner, but which is now being challenged, and outright discredited, by newer research and theories like the ‘double empathy problem’.

That, of course, hasn’t stopped them making money from their incorrect, outdated theories, or from continuing to preserve the myths that countless other so-called Autism “experts” have since adopted and promoted.

Much of Baron-Cohen’s research has been criticised for its selective nature, for his penchant for drawing conclusions from work that uses very small groups, and for his use of poorly conceived, often flawed tasks, processes, and methodologies.

That Baron-Cohen was not alone, that he had an ally in Uta Frith, with her distorted understanding of how Autistic people work, think, and feel, went a long way towards strengthening and perpetuating his own erroneous theories.

Put simply, Baron-Cohen, Frith, and others, have benefitted greatly from little more than ‘getting in on the ground floor’ and, alarmingly for Autistic people, from being able to ‘sell’ a compelling hypothesis.

The double empathy problem explains so much

Imagine living in a world where there was more than one prevailing point of view, or more than one ‘correct’ way to be. Autism researcher Damian Milton, himself Autistic, did so when in 2012 he proposed the ‘double empathy problem’ and blew giant great holes in the idea that Autistic people can’t possess a theory of mind.

As I have already outlined, thanks to flawed, outdated, but well publicised research, most non-autistic people who know little about Autism would likely have a stereotyped view of Autistic people as lacking empathy, when this is simply not true.

In my own research into theory of mind, the word ‘normal’ comes up repeatedly, as if there is essentially one preferred or correct way to be, and to my mind at least, that will always be subjective.

But this single point of view, this black and white, right and wrong perspective does mean the ill-informed and uninitiated will often view Autism as a defect to be ‘fixed’ or ‘cured’, rather than accepting it as a naturally occurring ‘difference’, with all the deeper meaning the word itself entails.

Milton’s theory of double empathy instead proposes that the difficulties Autistic people face in social situations arise because there is a mismatch in the way we communicate, form relationships, understand the world around us, and experience and display emotions when compared to non-autistic people.

This can cause misunderstandings and a lack of empathy that flows not in one direction, but both ways. In other words, it isn’t only that Autistic people can find it difficult to understand non-autistic people, but that non-autistic people can find it difficult to understand us!

It’s this disconnect and lack of insight into the others’ culture, for both Autistic and non-autistic people, that Milton calls a ‘double problem’.

From the moment we come screaming into this world, we are taught to behave in a single particular way and to learn non-autistic culture and communication, which is all well and good if you’re not Autistic. But what if you are?

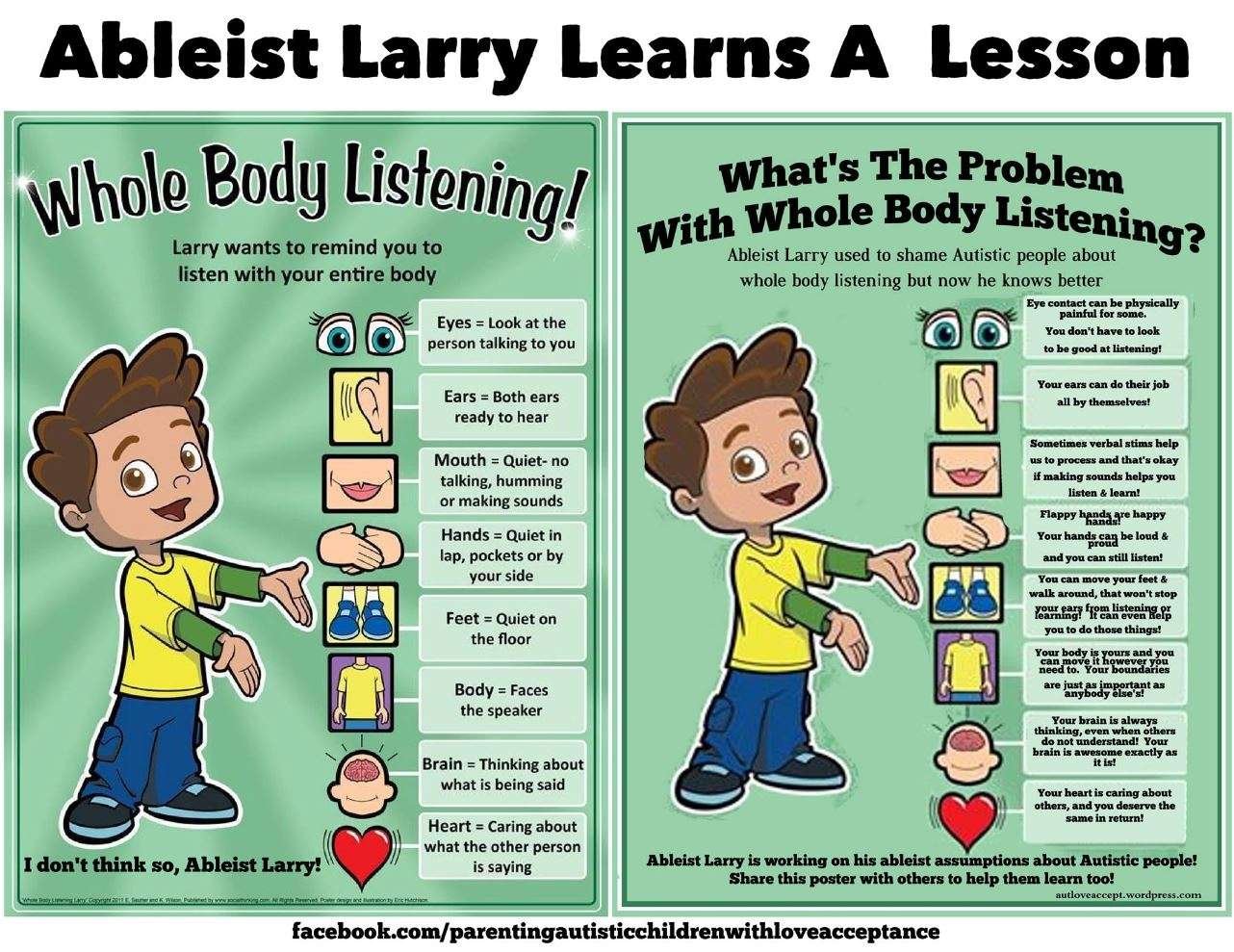

This is where problems can, and often do, begin for Autistic children, with many actually forced to adapt their natural behaviour to the types of behaviours educators, the school system, and even health professionals deem acceptable.

Even in 2023, few places teach anything other than neuronormative communication styles. A quick online search will turn up plenty of courses that teach communication skills to Autistic people, but trying to find courses that teach non-autistic people about the ways Autistic people communicate is a completely different story.

This is just one example that demonstrates how non-autistic people do not generally expect to have to understand or learn Autistic perspectives, which, if you ask me, sounds like pretty good evidence of a lack of empathy. (Just saying…)

So, as I see it, it isn’t a stretch to suggest that a lot of what has traditionally been seen as communication “problems” or “difficulties” for Autistic people, are in fact simply communication differences.

This idea grows even deeper roots when you consider that many recent studies have found that Autistic people’s social and communication issues are not present when they interact with other Autistics.

For example, in the game “telephone,” in which people whisper a message from one person to the next, chains of eight Autistic people are able to maintain the integrity of the message just as well as eight non-autistic people do.

It’s only in ‘mixed’ groups of Autistic and non-autistic people that the integrity of the message degrades.

There’s no doubt part of the problem for Autistic people will always be that it’s a numbers game, as is the case for all minorities – with the smaller population having to adapt and conform to survive within the wider community.

For myself, I had to “pretend” I was non-autistic for what will ultimately end up being the majority of my life, simply because I didn’t know any better, even though I always felt that there was something more going on inside.

It will of course also be difficult to find agreement on views, behaviour, and even terminology within the Autistic community, and some of this will depend on the time period when a person was diagnosed and their age at diagnosis.

Researching the topic ‘theory of mind’ has, for the first time, actually left me glad that I wasn’t diagnosed Autistic as a child. Even if it has been incredibly painful, confusing, and invalidating trying to live my life as someone I’m not, I count myself fortunate to have avoided potentially being sent to an institution, or experimented on, or worse.

I did eventually cobble together a career of sorts (at a cost, yes), I met a woman and fell in love with her and married her, I had a family.

It’s impossible to say whether or not I would have ‘achieved’ these things had my diagnosis come thirty, forty, or even fifty (now I am showing my age!) years earlier. But what is certain, is that I now have the kind of perspective I would otherwise never have had.

I have been Autistic my entire life, but it is also brand new to me. That gives me distance and allows me to see what others might not necessarily be able to.

For example, while some Autistic people (and almost all non-autistic people) might describe themselves as having Autism, I never would, because that suggests there is a cure for Autism, when there isn’t. I also wouldn’t ever say that I’m Asperger’s, even though, at some point in history, not very long ago, that is indeed how I would have been diagnosed.

It sure does make for murky waters – a quick online search for anything relating to Autism can leave a person completely lost and genuinely questioning what the truth is.

Perhaps it’s the case, like Autism itself, that “the truth” will remain specific for each Autistic individual.

But it sure would be nice to believe that those doing the research (traditionally non-autistic, white men – basically the opposite of diverse) would in future at least, as a starting point, consider Autistic people to be real life, thinking, feeling, empathetic human beings. Which is precisely what we are. Dammit.

Nothing about us without us

With all the controversy around the ways many researchers have traditionally viewed Autistic people, and the wider societal issue of placing the burden of responsibility for Autistic / non-autistic misunderstandings solely on Autistic people, many Autistic activists have begun advocating for the inclusion of Autistic people in Autism research, adopting the slogan ‘Nothing about us without us’.

Throughout my working life I have had to read and interpret a lot of research, be it for indigenous organisations or even broadacre agriculture, and there is one notable constant: it is almost always carried out by people who are not a part of the specific minority they are researching and, most importantly, they do not generally consult with that minority – especially when it comes to forming policy positions and decision making.

So I’m not surprised by the historical nature of Autism and Autism research – more saddened by it.

As I dig deeper, and learn more, it appears that ultimately the Autism research space is yet another characterised by cherry-picked research and science to support already largely formed hypotheses, and to keep the funding dollars rolling in.

Perhaps what were once genuine, honourable (perhaps) intentions to explain and even assist Autistic people, drown in wave after wave of self-congratulatory grandstanding and research for research sake that dig into every remaining crevice in order to keep life’s greasy wheel turning, when much of what’s being researched in the first place could be better explained with a heavy dose of common sense. (See waste-of-money-and-time studies such as: Study shows beneficial effect of electric fans in extreme heat and humidity, and Older workers bring valuable knowledge to the job.)

The one actual fact amongst all the damaging stereotyping of Autistic people as non-feeling automatons is, surprise, surprise, that we’re all people – Autistic and non-autistic alike.

Which means that some Autistics will struggle with aspects of theory of mind and empathy. But guess what? So too will some non-autistic people.

I understand that the unravelling of a theory that largely made you who you are in your profession would come as a bit of a blow.

I even understand the continuing smokescreen to keep that myth going. After all, it worked for years for the tobacco companies. (Who could have predicted that link, hey? That ingesting something that goes into your lungs could ever have been the cause of lung cancer.)

But for the likes of Baron-Cohen the jig is now well and truly up, and has been for some time. And it will only become clearer how ridiculous the concept that Autistic people can’t possess a theory of mind or empathy is as the number of people diagnosed increases, which it inevitably will as our overall understanding and awareness of Autism continues to grow.

I think in all of this it’s useful to recall Frith first stumbling upon Premack and Woodruff’s paper on chimpanzees that I mentioned earlier in this story.

Perhaps it says something about her, and Baron-Cohen, and Leslie, that in asserting, from their research, that Autistic people don’t possess the same mental aptitude and abilities when it comes to feelings and empathy as chimps do, that they didn’t see a problem at the time of publishing. That they really didn’t believe this notion would in any way be damaging to Autistic people.

Or perhaps they simply didn’t care.

Did you find this article helpful? Did it resonate with you or in some way make you stop and think? Writing these pieces takes time and effort, and your support can make a real difference in helping to keep this content flowing. If you enjoyed this post and would like to read more articles like this in the future, please consider donating a small amount to help me cover the costs of running this website. I’m not in this to get rich (and trust me, I won’t! 😉), but your contribution helps sustain the effort that goes into crafting fresh, Autism-friendly content. Your support is greatly appreciated. Thank you!

Thanks a lot for your post. I’m still trying to figure out wether I and my child are autistic or not; and I’m kind of scared, that I will be told, I can’t be autistic, because I can socialise and have a good TOM. Perhaps it’s not even necessary to really find a word for my struggels. A word would not make them less hard. But I want to tell, that I did find joy in your words, and anger about how the world is structured around ideas that are taken for granted. I always feel that way when I think about property/ land ownership, cause I can’t see how people can really believe, that they can own a part of nature and ban other people to trespass “their” border – even so I understand our underlying needs of safety). I relate that feeling to my thinking about NT and Neurodiversity. And many other areas, too. We have to find a way as people to be more open and humble.

I’m stuck, so where did Sally look for the marble?

Hey Charles,

A correct answer answer to the ‘Sally-Anne’ task depends on your understanding that Sally did not see Anne move the marble to her box. That means Sally is going to look for her marble where she last left it: in her basket.

I also quite like this paper, which also discusses theory of mind and the ‘Sally-Anne’ task: https://www.bu.edu/autism/files/2010/03/2007-HTF-ToM1.pdf

I identify SO MUCH with so many of your experiences. I have also always been able to read people accurately and quickly, enough that my husband has referred to me as near clairvoyant. And yet, I actually had a psychiatrist tell me I couldn’t be autistic because I have empathy and social skills. I sought a second opinion. But my experience shows that even the ‘trained professionals” still are blinded by the outdated stereotypes in ways that are harmful to autistic people. And as I advocate for my autistic son, to have his differences recognized and acknowledged as just as acceptable as neurotypical behaviors, I remind people that autistic kids grow into autistic adults. And that we matter too.

Thanks for your comments Sara. I reckon the more we can do to raise awareness about what Autism actually is, the better we’ll all be off. Very sorry to hear about your experience with the psychiatrist, but it was mine as well. Soooooo glad to hear that your son has you to advocate for him. We need plenty more advocacy and validation to help bring about change, too!

An excellent post, thank you 🙂

Thanks Esmerelda – glad you enjoyed reading it.